Main exhibits of the subject: Rome 1883; Berlin 1886; Palermo 1891.

Sought after by international collectors and enthusiastically welcomed by some of the most influential intellectuals of his time (Gabriele D'Annunzio above all), Costantino Barbella's production is effectively summed up by the four terracotta items presented here. In the small-sized sculptures, the artist fully expressed his creativity [1], marking an era with his visual universe populated by Abruzzese shepherds and farmers, protagonists of a rediscovered Arcadia. The sculptures he created in his youth were particularly successful, starting from the years of training spent between his native Chieti and Naples, where he studied under the wing of Stanislao Lista (former teacher of the contemporary Vincenzo Gemito). It was precisely at the Neapolitan exhibitions of the mid-seventies of the nineteenth century that Barbella recorded the first successes that forced him to the attention of critics: think, for example, of the exhibition of the promoting company "Salvator Rosa" in 1874, where he presented the group The joy of innocence after work , a work that first entered the personal collections of Vittorio Emanuele II, then in the public collections of the Capodimonte Museum, where it is still kept today.

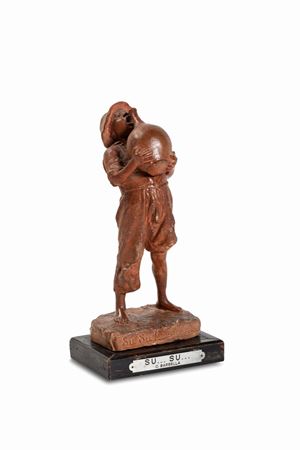

Critics appreciated the originality and narrative value of the subjects of Barbella's terracottas (which in some way reflected the taste for genre scenes of transalpine realism), the capacity for psychological introspection and the subtlety of the smallest details. Vive praises were also addressed to him in recognition of an uncommon technical expertise in directing the bronze castings, which were commissioned even many years after the creation of the first examples. At the root of the special attention paid to the patination of surfaces [2] and the rendering of the chiselling, a sort of remote comparison with the Neapolitan Vincenzo Gemito, who in those same years shared with Barbella the primacy of the new southern school of sculpture. Only in rare cases, however, did the two artists deal with similar subjects: among these the terracotta entitled Su su! ... ( lot 106 ), made in 1882, should be remembered, one year after the famous Acquaiolo of Gemito. In both cases, the theme of water is associated with the image of a child of the people: classical that of the Neapolitan sculptor, vividly anecdotal that of the Abruzzese. It is a recurring iconography in Neapolitan art of the late nineteenth century, also in painting (think of the painting by Vincenzo Caprile of 1884 Zurfegna water in Santa Lucia, now in the National Art Gallery Moderna di Roma), sometimes used by artists with the programmatic intent of citing pieces of ancient sculptures carefully studied at the Archaeological Museum, located a few steps from the Academy of Fine Arts. Although in Su su ..! the reference to antiquity is apparently not as explicit as in the Gemitian Acquaiolo, the criticism of the time, however, saw in it a naturalness similar to that of certain Hellenic sculpture. The poet Gabriele D'Annunzio, in a review of the Berlin exhibition of 1886 published in "La Tribuna" under the pseudonym "duca Minimo", wrote about the bronze version of the work: «And who does not know the Su su ... , that figure of a child who tries to drink from a flask that is too heavy, very elegant, full of life, almost perfect like a small masterpiece of the good Greek time? " [3]. The fame of the work was undoubtedly due to the success it had at the "Exhibition of Fine Arts in Rome" in 1883, where Barbella presented nine sculptures, including bronzes and terracotta. Among these was Armonia ( lot 108 ), exhibited there in the bronze version then purchased by the former chedivè Isma'il Pascià. The work was set as a return to the theme of the group The song of love, exhibited in Naples in 1877 at the National Exhibition of Fine Arts (in the same venue his friend Francesco Paolo Michetti presented The Corpus Domini procession in Chieti), a work which, as he later recalled, gave him "money and fame" and "the moral satisfaction of being appointed, for special merits, unique among exhibiting sculptors, honorary professor of the Royal Institute of Fine Arts "[4]. The success of the group pushed Barbella - as well as making more bronze castings - to create new sculptures inspired by the same iconography, in which the natural grace of the Abruzzo peasants is cloaked in musical suggestions. In Armonia the sculptor takes up two of the three figures of The love song intervening with slight modifications on some details of the pose and the clothes, and dwelling on the pictorialism of the details, a goldsmith's approach that suggests the preciousness of the painting of the Catalan Mariano Fortuny y Marsal.

Despite the tendency to exalt the decorative aspects of the work of art, however, Barbella's sculpture at the turn of the new century did not seem to be seduced by the new languages of international liberty. The only work in which literature has identified an update in the modernist sense of Barbellian production is the terracotta entitled Ebbrezza (Chieti, Costantino Barbella Art Museum), depicting a sensual female nude lying on a bed adorned with roses. Made in 1912 and exhibited to the Neapolitan promoter the following year, the work was at the end of a long creative process started in 1907, as documented by the terracotta presented here (lot 107 ). Signed, dated and placed by the artist himself on the base ("Rome 1907"), this terracotta sketch is therefore to be understood as a first idea for Ebbrezza, which in the final version will see the pose of the woman unchanged from the half-open mouth as in ecstatic rapture. Before returning to the theme for the final sculpture, Barbella re-presented the subject of the sleeping woman in Happy Dreams, completed in 1908, and took it up again later, freed from its erotic connotations, for a head of Santa Cecilia, completed in 1915.

Manuel Carrera

November 2020

[1] On the subject, see: P. Oran, Un grande scultore di statue piccine: Costantino Barbella, in “Il Secolo XX ", September 1906, pp. 706-719; A. Amoroso, Il grande scultore del piccolo, in “La patria degli italiani”, 9 December 1925.

[2] Cfr. A. Lancellotti, Costantino Barbella (1852-1925) , Rome 1934, p. 73.

[3] Duca Minimo [Gabriele D'Annunzio], Arte ed artisti. Costantino Barbella , in “La Tribuna”, June 3, 1886.

[4] Taken from the memoirs of Barbella published in O. Roux (edited by), IIllustri italiani contemporanei: memorie giovanili autobiografiche di letterati, artisti, scienziati, uomini politici, patrioti e pubblicisti, Florence 1908, vol. II, second part, pp. 185-186.