33

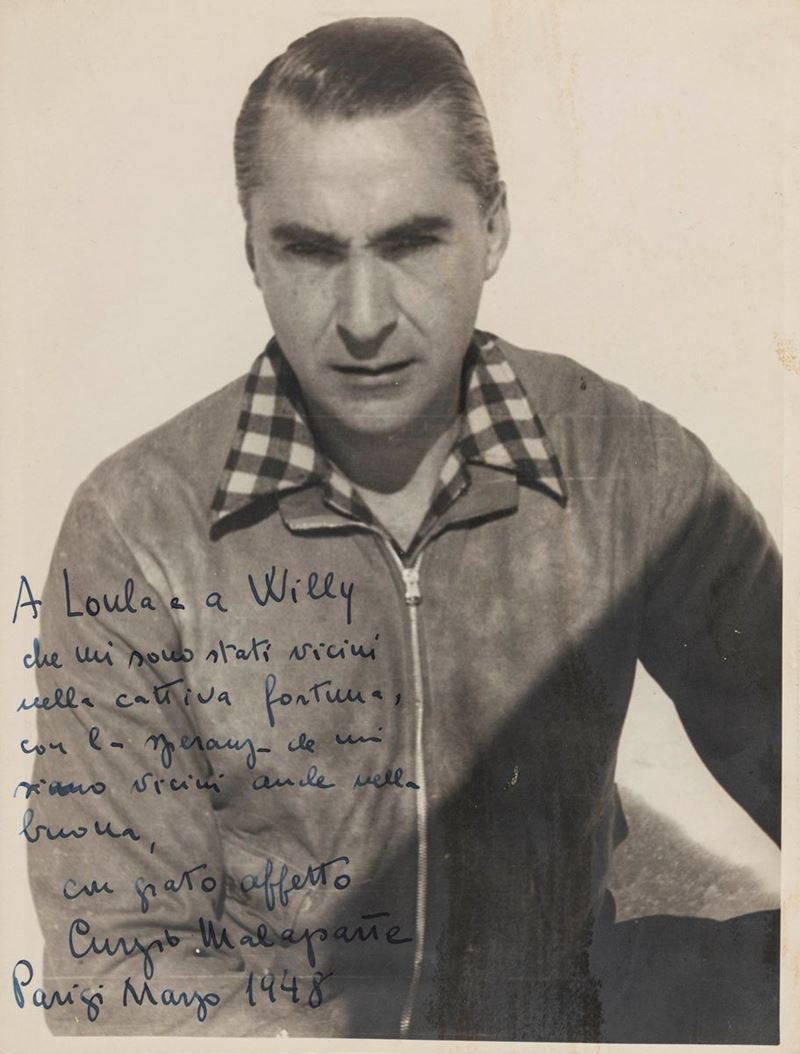

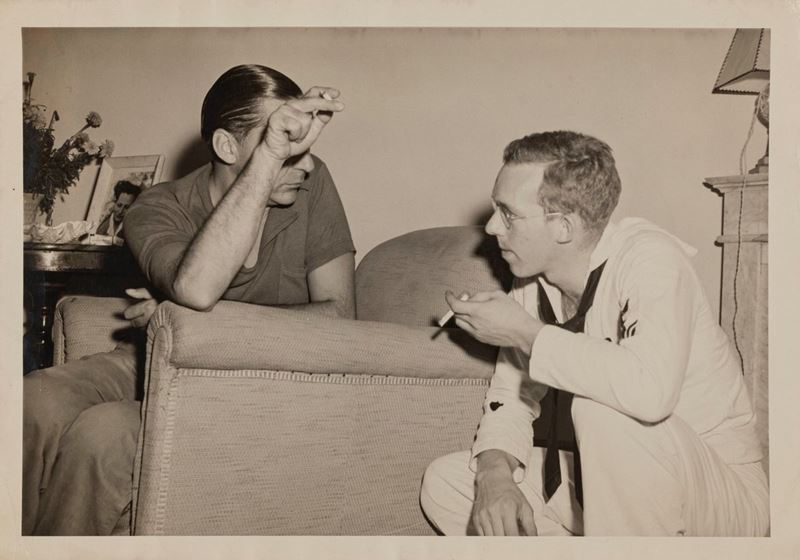

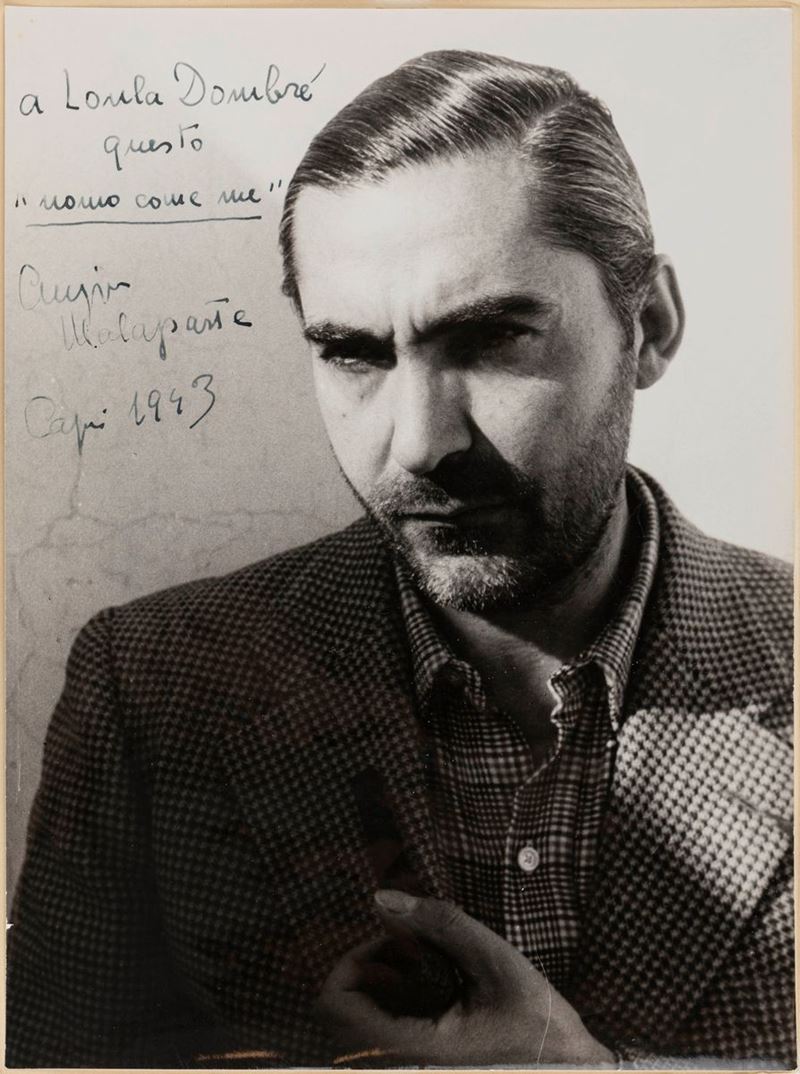

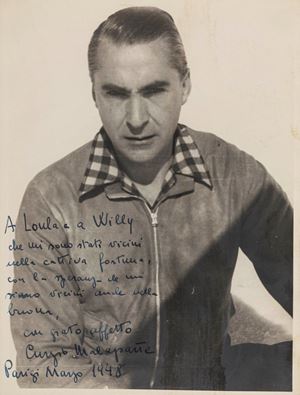

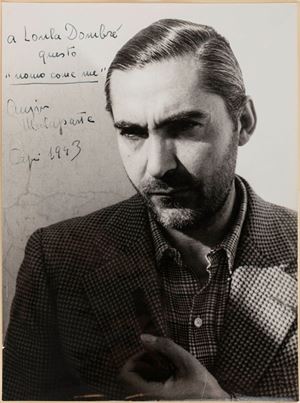

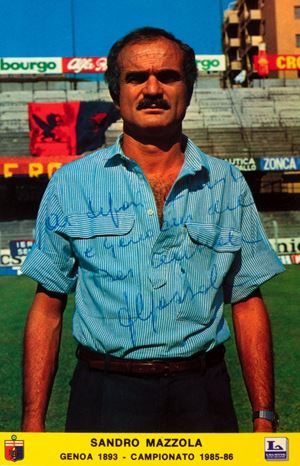

Malaparte, Curzio / Laprade Dombré, Loula

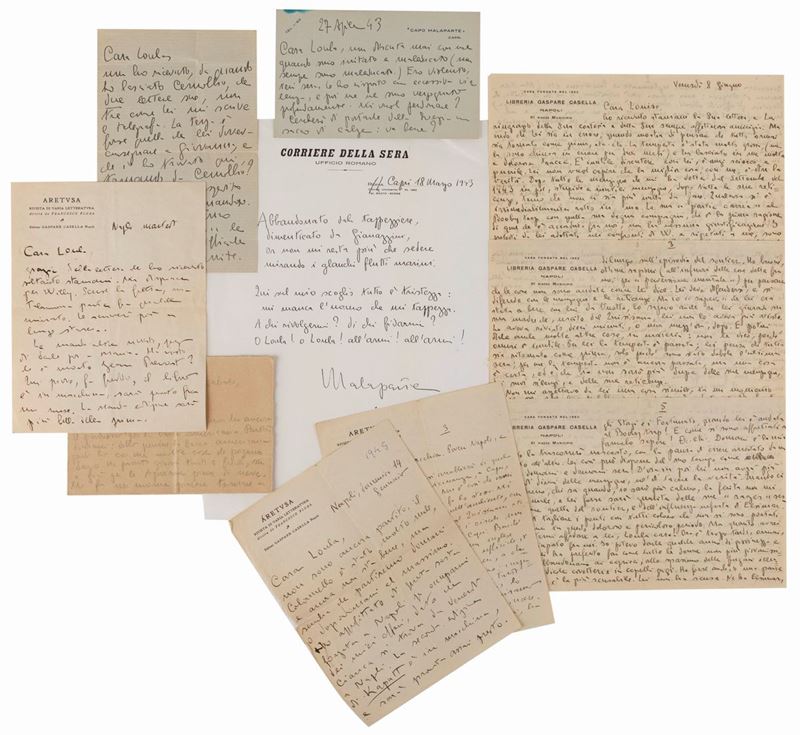

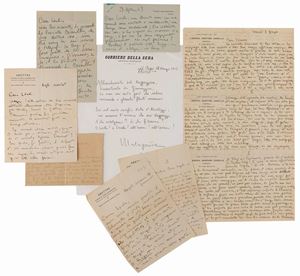

Correspondence, typescripts, postcards, photos, telegrams, 1943

Estimate

€ 11.000 - 13.000

Sold

€ 16.380

The price includes buyer's premium

Do you have a similar item you would like to sell?

Information

Specialist Notes

All this to underline how in this UNEDITED correspondence the story of a man and a woman, Loula ( Loula Dombré , a splendid Franco-Guatemalan lady, wife of an important hotelier in Capri from whom I had been a guest Malaparte) and Curzio, against the backdrop of a difficult, terrible but also tremendously true. A story that few know because jealously kept between the lines of this copious correspondence, a story that their friends knew well, but that perhaps few imagined so rich and profound. & Nbsp;

A love story, of course, but it is simplistic to label it this way: Loula and Curzio are linked from the first moment in which they know each other by a" heavenly correspondence of loving senses ", a union so intimate that we understand Curzio did not want to set it apart from others. Between these lines there is all of Malaparte, his fervor, his anger, his disappointment, his impulses, his passions, his whole universe so complex and problematic, however, dissolved in the clear epistolary prose, which always tends to grasp the moment, to fix the emotion of the moment in the form of brief and icastic statements. Loula is his alter-ego, it is the mirror in which Curzio wants and longs to reflect himself, to understand himself and the world around him. And even when he wearily reviews the worldly life of his Capri, Curzio never ceases to amaze us and tell about himself in the bodies of others.

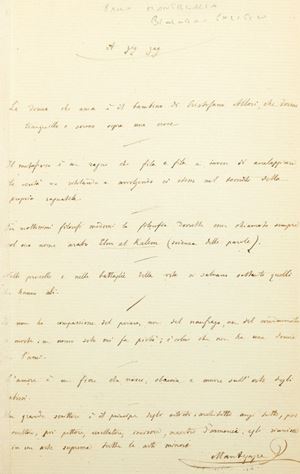

It is difficult, I would say impossible, to summarize the 82 handwritten and typewritten letters that make up this correspondence, a total of about 120 pages that unfold between the beginning of 1943 until April 1957: fifteen years lived really intensely, both for Curzio and for Loula, and I would say for the whole of Italy , which emerges clear and vivid here.

Some excerpts like rapid bird's eye views. & nbsp;

There is a letter torn, typewritten on blue paper, of which only a page and a half remains, but where we read: “One day we will know what we have done, and I will want to see the faces of those cowards of Capri! I beg you, indeed, I impose you, to burn this letter immediately. The war is virtually over, but it's not over. Obey me dear Loula. Perhaps I was wrong to write this to you. Obey me, at least, if you want to give me proof of affection. Know, in short, that the Americans went on a rampage when they learned that I had been arrested [deleted parts follow]. This does not mean that I will not have trouble in the future: they will try to annoy me again. But I will be able to defend myself, and then, in a year at the most, this whole system of arrests, trials, etc. it will end and then ... "Of six pages, only three scarce remain, Loula did not obey (luckily for us) the order to burn it and so we are left with traces of this delicate moment in Malaparte's life. We are certainly in 1943 close to the Roman arrest, and these are really difficult years. In another letter dated 23 June (presumably from 1946), he delivered to Loula through a mutual friend "a package containing a silver fox and a platinum fox inside. (….) I don't know how my things will turn out. I must expect all the violence and all the possible injustices, especially after the latest changes. And I think it is better to provide, to take the necessary precautions. If a misfortune happens to me, I should think of a lawyer for my defense. And it takes a great lawyer. But a great lawyer, today, does not accept if he does not have a large advance. One hundred or one hundred and fifty thousand lire. Can you try to sell my foxes? The price is high but I would settle for 150,000 lire for both. (…).

But then the war ends, and the sign of the newfound “normality” is the desire to dance. Monday 9 August 1948: "Dear Loula and dear Willy ... Edda dances every evening, in the midst of a small court of collaborating Roman princes, who dance in a black silk shirt, gold belt, and white trousers, as in the past . Fascism turned snobbery. Who would have imagined it! " The Edda mentioned is obviously Edda Ciano, from home in Capri. The Capri he describes is a treasure trove of contradictions, between former fascists, collaborators, diehards, Italian and foreign viveur etc. And the rediscovered normality is also an old Camus described as follows: (February 23, 1950), "Camus is getting older and older, he repeats things every five minutes, repeats the same questions a hundred times, and he bores everyone, because he can't keep quiet, and then he talks nonsense, with that idiotic worldly spirit that gets on my nerves so damned. It is a kind of Ivancich in trousers. He doesn't want to leave, and I'll keep him until Christmas! But basically he is a good man, and he loves me. I understood what it is: it is a pique -assiette . He is here because he saves so. And after all, he only has a pension to live on. (...) "Camus defined as a nice and honest" scrounger "is really the best!

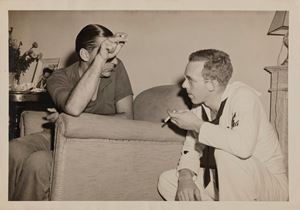

In addition to the correspondence, the lot is enriched by several telegrams, postcards, three beautiful photographs with dedications, articles and various newspaper clippings but above all three typewritten texts, two of which are unpublished. To all this are added 12 volumes of Malaparte, almost always first editions, 7 of which bearing heartfelt dedications.

A whole that excites, not only for those with a passion for the writer Malaparte but I would say for the ability it has to illuminate - with a unique expressive power - some of the key years of our past Italy.

& nbsp;

Contact

Suggested lots

Caricamento lotti suggeriti...